Description

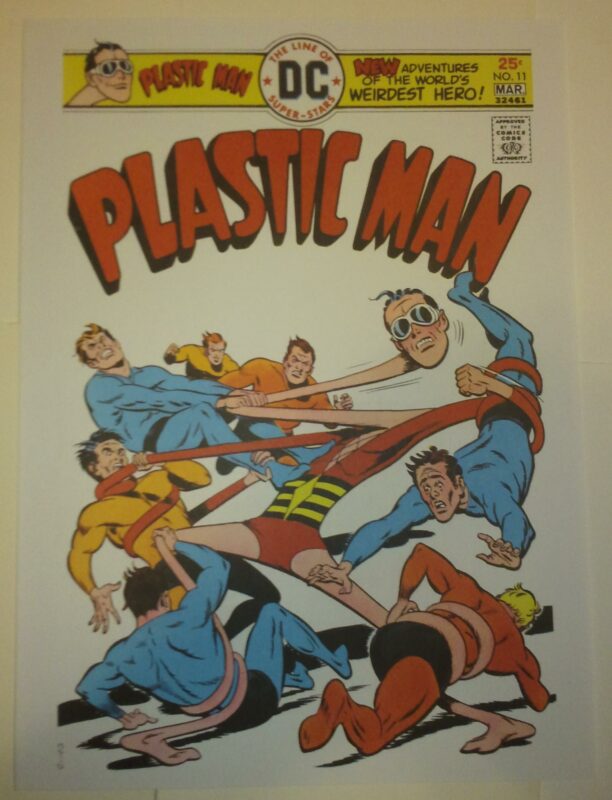

In 1956, DC acquired many characters from the venerable Golden Age publisher Quality Comics – including several romance titles, the ace aviator known as Blackhawk, and the super hero Kid Eternity. The jewel in the crown, by a wide margin, was Plastic Man, cartoonist Jack Cole’s begoggled, hyperpliable crime-fighter, also known as “the longest arm of the law.” Zany humor had always been a hallmark of the character, dating back to his 1941 debut, so a late-1960s revival in the campy spirit of the then-popular Batman TV series seemed appropriate. While the new series fizzled in 1968 after just ten issues, Plas refused to curl himself into a ball and roll away. He was resuscitated eight years later, picking up right where he left off in issue #11, with DC’s resident offbeat-hero chronicler Romana Fradon supplying the eye-catching cover and interior art. “I enjoyed drawing Plastic Man because he was goofy- not ‘serious’ like other super heroes,” Fradon said. That was evident from this issue’s title, “The Hamsters of Doom,” a tale of “action, adventure, neuritis, and nostalgia” that has the contorting crusader and his doltish sidekick Woozy Winks battling an evil genius who can transpose people’s minds into the bodies of laboratory hamsters. Plastic Man (Patrick “Eel” O’Brian) is a fictional comic-book superhero originally published by Quality Comics and later acquired by DC Comics. Created by writer-artist Jack Cole, he first appeared in Police Comics #1 (August 1941). One of Quality Comics’ signature characters during the Golden Age of Comic Books, Plastic Man can stretch his body into any imaginable form. His adventures were known for their quirky, offbeat structure and surreal slapstick humor. When Quality Comics was shut down in 1956, DC Comics acquired many of its characters, integrating Plastic Man into the mainstream DC Universe. The character has starred in several short-lived DC series, as well as a Saturday morning cartoon series in the early 1980s, and as a recurring character on Batman: The Brave and the Bold. Although the character’s revival has never been a commercial hit, Plastic Man has been a favorite character of many modern comic book creators, including writer Grant Morrison, who included him in his 1990s revival of the Justice League; Art Spiegelman, who profiled Cole for The New Yorker magazine; painter Alex Ross, who has frequently included him in covers and stories depicting the Justice League; writer-artist Kyle Baker, who wrote and illustrated an award winning Plastic Man series; artist Ethan Van Sciver has an affinity for the character as he always toys with the idea of launching a regular monthly Plastic Man series and often draws him for fun, and Frank Miller, who included him in the Justice League in the comics All Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder and Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again. Plastic Man was a crook named Patrick “Eel” O’Brian. Orphaned at age 10 and forced to live on the streets, he fell into a life of crime. As an adult, he became part of a burglary ring, specializing as a safecracker. During a late-night heist at the Crawford Chemical Works, he and his three fellow gang members were surprised by a night watchman. During the gang’s escape, Eel was shot in the shoulder and doused with a large drum of unidentified chemical liquid. He escaped to the street only to discover that his gang had driven off without him. Fleeing on foot and suffering increasing disorientation from the gunshot wound and the exposure to the chemical, Eel eventually passed out on the foothills of a mountain near the city. He awoke to find himself in a bed in a mountain retreat, being tended to by a monk who had discovered him unconscious that morning. This monk, sensing a capacity for great good in O’Brian, turned away police officers who had trailed Eel to the monastery. This act of faith and kindness—combined with the realization that his gang had left him to be captured without a moment’s hesitation—fanned Eel’s longstanding dissatisfaction with his criminal life and his desire to reform. During his short convalescence at the monastery, he discovered that the chemical had entered his bloodstream and caused a radical physical change. His body now had all of the properties of rubber, allowing him to stretch, bounce, and mold himself into any shape. He immediately determined to use his new abilities on the side of law and order, donning a red, black and yellow (later red and yellow) rubber costume and capturing criminals as Plastic Man. He concealed his true identity with a pair of white goggles and by re-molding his face. As O’Brian, he maintained his career and connections with the underworld as a means of gathering information on criminal activity. Plastic Man soon acquired comedic sidekick Woozy Winks, who was originally magically enchanted so that nature itself would protect him from harm. That eventually was forgotten and Woozy became simply a dumb but loyal friend of Plastic Man. In his original Golden Age/Quality Comics incarnation, Plastic Man eventually became a member of the city police force and then the FBI. By the time he became a federal officer, he had nearly completely abandoned his Eel O’Brian identity. Appearing in the first 102 issues of Police Comics, Plastic Man was originally a 6 page story, then a 9 page, then a 13 page and later a 15 page story, the lead feature of Police Comics and one of the most popular characters of his era. When Plastic Man was awarded his own 52 page comic to be released quarterly, beginning in 1943, Cole could no longer do everything. Other hands inked, wrote or did backgrounds, while Cole tried to oversee as much of the strips as possible. He was also doing Midnight, The Spirit and various other strips during the 1940s as well. Not only the artwork was unique, but Cole’s scripts were breaking new ground as well. Beginning in Police #19, Cole peppered his stories with plots and characters unlike anything seen in other comics, a considerable feat considering how many publishers were then doing super-heroes. In Police #19, Plastic Man finds himself in a “forest of fear” surrounded by the mechanical devices of a mad scientist. Near the climax of the story, Plastic Man, the scientist and 3 other men are surrounded by a ring of fire that is expanding and closing in. Believing their lives to be over, each man confesses crimes in his past that he has kept secret. Plastic Man then reveals his secret identity as Eel O’Brian and confesses he is wanted in 8 U.S. states for crimes too numerous and varied to mention. In the end he lets four criminals go free, something no other hero of the day would have done. Ramona Fradon (born October 1, 1926) is an American comic book and comic strip artist, known for her work illustrating Aquaman and Brenda Starr, and co-creating the superhero Metamorpho. Her career began in 1950. She landed her first assignment on the DC Comics feature Shining Knight. Her first regular assignment was illustrating an Adventure Comics backup feature starring Aquaman, for which she co-created the sidekick Aqualad. Following her time with Aquaman, and taking a break to have her daughter, Fradon returned to co-create Metamorpho, drawing four issues of the series. She returned briefly to design a few covers for the title. Fradon was inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2006.

Looks Like DC’s Plastic Man Movie Is Back On Track, And With A Big Change

Though the MCU has definitely reigned supreme at the box office in recent years, moving forward, Warner Bros’ DC universe does look like it’ll set itself apart and possibly benefit from its more offbeat choices coming down the pipeline. There’s a noir version of Gotham coming in The Batman and a wacky war movie with James Gunn’s The Suicide Squad. And among the other projects in development over at WB, the Plastic Man movie is moving forward, but with a stretchy new course.

Now this decision might ask fans to get real flexible. Plastic Man has been in the works over at the studio since 2018, but its latest update is a new writer and direction. Instead of Amanda Idoko writing the action comedy, another newcomer, Cat Vasko, will be working on a version of the project that will feature a female lead. It’s unclear whether the DC hero will be portrayed as a woman. Following the Elisabeth Moss-led The Invisible Man, it’s possible Plastic Man just might not be told from the perspective of the hero.

Plastic Man originally started as a Quality Comics character in 1941 before the elastic-powered hero moved to DC when its prior publisher sunk. As the story goes, Patrick “Eel” O’Brian was part of a gang until he is left for dead by them during a heist-gone-wrong, which left him soaked in an unknown chemical liquid. This results in him gaining the power of elasticity (like Fantastic Four’s Mr. Fantastic or The Incredibles’ Elastigirl), along with regeneration, invulnerability and slow aging. O’Brian becomes a police officer in between his superhero antics.

The comic book character is well-loved for his silly demeanor and tendency to provide the Justice League with comedic relief. Ben Schwartz has famously been fan-casted in the role, who has championed his interest in the character too, calling its potential at the likes of Deadpool’s maximum effort. Marlon Wayans also threw his hand out in interest of taking on the role last year.

This development will almost certainly have fans firing back at Warner Bros for the female-led pivot, especially since The Hollywood Reporter story does not offer much context about what the vision is for the project. There’s a lot different ways DC could introduce the hero, but gender-swapping the character when Plastic Man has never once been a woman in the comics might lead to failure in terms of alienating its fanbase. As mentioned, my gut here is Plastic Man would have to be in a Plastic Man movie, but perhaps the framing of the film will be shifted.

Related products

-

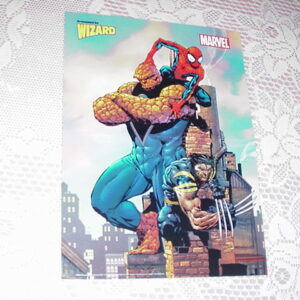

Ultimate Spider-Man Thing Wolverine Poster David Finch X-Men Fantastic Four

$29.99 Add to cart -

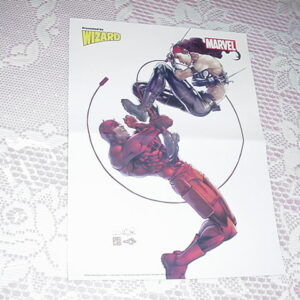

Daredevil vs Elektra Poster Ultimate Salvador Larroca

$29.99 Add to cart -

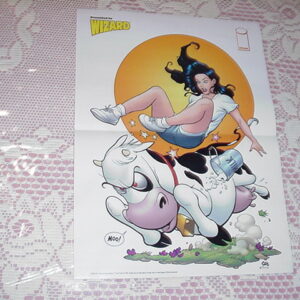

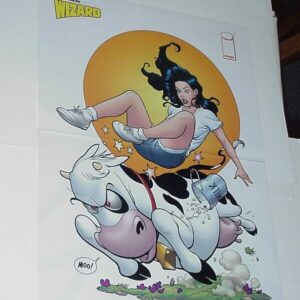

Liberty Meadows Poster # 1 The Cow vs Brandy by Frank Cho University2

$29.99 Add to cart -

G.I. Joe Poster # 3 Cobra Commander Storm Shadow vs Snake Eyes and Billy by Mike Zeck

$34.99 Add to cart