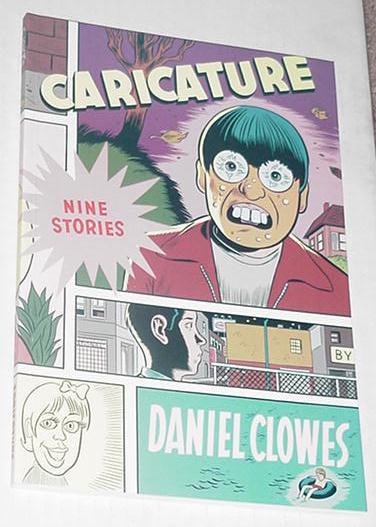

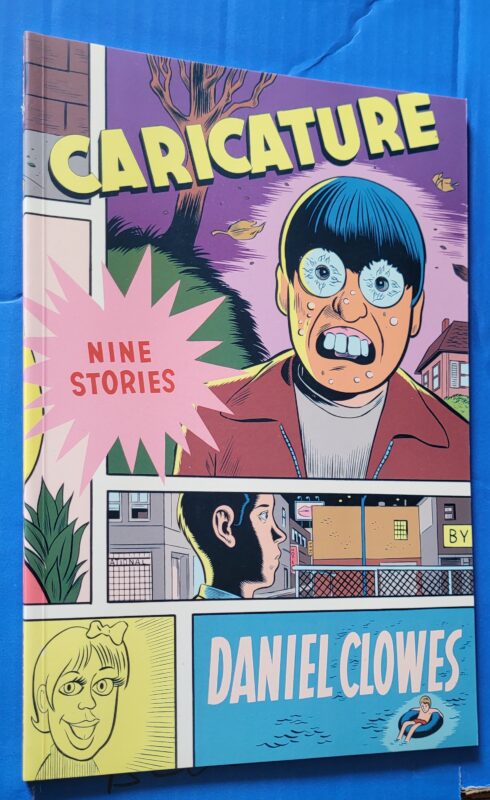

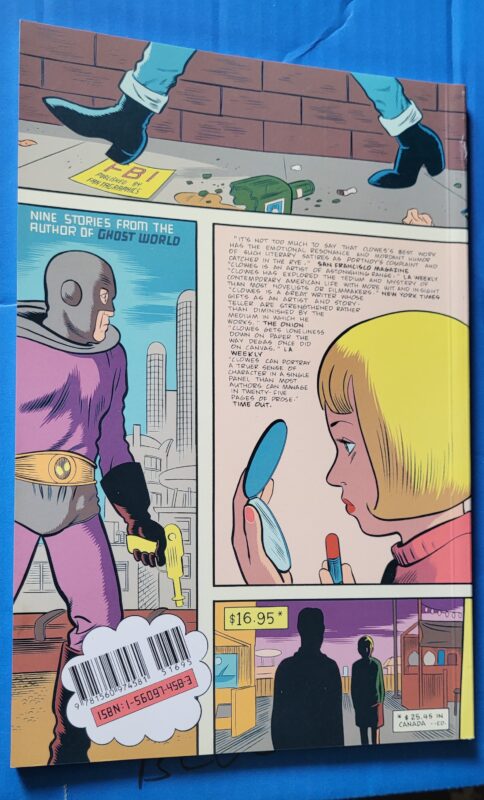

Caricature Nine Stories TP Daniel Clowes Green Eyeliner Blue Italian

$69.99

Description

Caricature Paperback

by Daniel Clowes (Author)

From the author of Ghost World and Patience. Anchored by the title story, Caricature also includes eight other stories, including “Green Eyeliner,” “MCMLXVI,” the full-color “Gold Mommy,” “Glue Destiny,” “Gynecology,” “Immortal, Invisible,” “Blue Italian Shit,” “Like a Weed, Joe,” “Black Satin,” and more.

“I wish every one of my favorite cartoonists would produce a version of this book: a handful of short stories, all distinct in style, yet all unified by the artist’s singular sensibility. A master class in concision and characterization, with seemingly endless tectonic layers of implication.” – Adrian Tomine

These nine stories show Clowes (Ghost World) as a writer compelled to produce infinite variations on the inner monologues of articulate, geeky loners. His characters exude a stylish, contemporary misanthropy; they’re self-isolated, bland and ordinary, straight from some small town or emotionally dead family; and admittedly and intensely self-involved. They invariably substitute a trendy obsession with media kitsch, porn, fashion, old folk music or with just looking bored for empathetic communication or even small talk with others. These personages seem depressed and are usually fed up with most people. Though saturated in this tone of mannered disdain, Clowes’s pieces are rescued from cliche and repetition by his expressive, meticulously glum drawings (in b&w and color) and a constant undertone of oddball, mocking hilarity. In the title story, he provides a portrait of an itinerant, county fair caricaturist and the unstable hipster brat-chick who insinuates herself into his life. In “Blue Italian Shit,” he relates the story of Rodger Young, secret virgin and pathetic poseur, and his journey through a succession of bad late-1970s New York City styles (“there were fifteen minutes on this earth when I had a John Travolta haircut”) and peculiar roommates (“Nat… listened to Kansas, and walked around naked”). In the supremely weird “Gynecology,” Clowes deftly generates his characteristic emotional anemia in a story featuring a singing gynecologist and racist iconography. Clowes is a strange master at creating entertaining scenarios about contemporary social vacuity.

Paperback: 100 pages

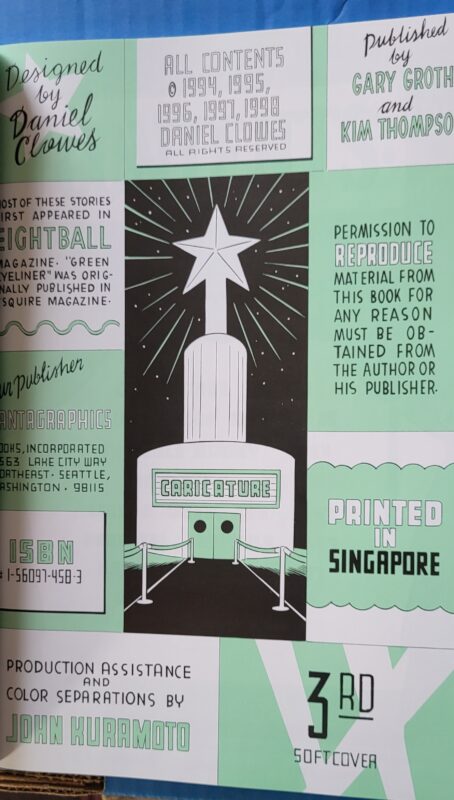

Publisher: Fantagraphics

Dan Clowes’ ‘Caricature’ (2002) collects nine illustrated stories, all of which are characterized to varying degrees by Clowes’ distinct brand of perception, wit and vision.

The most impressive story included is the black-and-white ‘Immortal, Invisible,’ which the cover art wisely celebrates and places center stage.

‘Immortal, Invincible’ is a simple but highly insightful narrative of a thoughtful, friendless fourteen year-old boy’s somber adventures on Halloween night. ‘Carmichael,’ as he calls himself since he dislikes his given name, ‘David,’ realizes he’s probably too old to go “trick-or-treating,” but doesn’t want to “squander this one last opportunity…”, especially as he sees the effort as “sort of a spiritual thing.”

And so in a “strange adolescent mood,” David walks the isolated streets of the town in a hideous mask, vaguely seeking “a strong sense of fellowship,” but encountering indifference, contempt, mockery and some thick-skinned adults blissfully or blandly locked into their own existences, such as the woman who flips a spoonful of peanut butter into his trick-or-treat bag with a loud “thok” while saying to her friends, “Kids love the creamy goodness of peanut butter.”

David also encounters a kindly mature couple who invite him into their home, where he is offered “a suspect plate of wafers” and an opportunity to work an old puzzle of the United States while the wife monologs about “various religions of the world.” Her conclusion, as the boy understands it, is that “while each has its merits, none was really worth a damn.”

After observing the loneliness and isolation of almost everyone he encounters, and quietly reversing his thoughts, actions and reflections several times, David makes peace with his mood and the non-events of the evening, and goes home, resigned but presumably better for having spent the evening as he has, since, in the liminal space of the street on the most liminal night of the year, he has been, however briefly, both ‘immortal’ and ‘invisible,’ a comfortable state of being that he may never experience again in the daylight ‘adult world’ lying just ahead.

The title story covers several days in the life of itinerant caricature artist Mal Rosen as he plies his trade at a fair in Twin Lakes. Due to his choice of professions, Mal has to stare at common-looking and ugly people all day long and attempt to flatter them verbally and artistically in some small way. Most of the time he succeeds in his effort, but occasionally he surrenders to both reality and despair and draws the person as he actually sees them or, going further, depicts them in the worst possible light.

Mal, who on occasion likes to imagine he’s having sex with his female customers, says, “I would never admit it but I guess deep down I want to be rich and famous and loved by all the beautiful women…” On his second day, he encounters Theda, an alternately depressed, blase, and explosively hostile young woman who is “paid to dress up and go to night clubs and look cool” by promoters. Theda’s father is modern artist “Rambrent” of the “Essentialist” School, and Theda (who is clearly an early model for the Enid Coleslaw of 1997’s ‘Ghost World’) is correspondingly ‘arty.’

Theda enthusiastically believes Mal is a genius, plays pranks on him and has intercourse him in his hotel room, but then doesn’t return after listlessly strolling away for “a hot dog or something.” Mal has clearly been nothing more than a brief diversion for Theda, and her infatuation with him has ended as abruptly as it began. It’s possible that Mal has already become less than a distant memory in Theda’s fickle psyche.

The continual effort to confront and transform mankind directly through his craft makes Mal literally bleed, the result of his hand constantly rubbing against the rough drawing paper he uses. But Mal’s ‘bleeding’ is also symbolic: Mal has become something of a ‘sin-eater’ for the rest of mankind over the course of his career. Towards the end of Mal’s story, a couple set their “deformed” child before him, and he asks the reader, “What kind of person takes a deformed child to a caricaturist?” Such double negatives, hard truths and insensitivities are a terrible burden, and leave Mal an apparently broken man by the story’s close.

‘Green Eyeliner,’ “featuring Mona Beadle,” is about a neurotic young misanthrope who believes she was “born to be a widow.”

Believing herself to have been “fat and just completely horrifying in every way” during high school, where she was made an object of fun by some of the other students, Mona has ‘reinvented’ herself as a beautiful girl with a blond Louise Brooks hairdo, one who has very vague hopes of some kind of a career in the arts.

Mona now sees herself as “one of the most glamorous and striking women in the world,” with her own “unique style, and poise, and confidence,” and enjoys posing with a gun, even if the gun is a fake one.

Quietly and conflictedly obsessed with handsome Gavin, an ex-schoolmate who now has a minor role on a local soap opera, Mona has come to reject “gay guys,” her former chosen group of companions, because “I need to be the hateful misanthrope in a relationship.”

Mona has come to prefer the company of Robert, who Mona classifies among “straight guys who just seem gay.” Nonetheless, Mona refers to Robert as a “totally repressed shut-in who knows literally everything about every stupid move, TV show, etc….”

Sociopathic Mona, who is clearly not getting the attention she wants from the world, declares that she seeks “absolutely nothing more than to destroy the world” and watch others “suffer, alone and miserable,” which she quietly declares is a state which reflects her own isolated existence. “Green Eyeliner’ is a subtle meditation on rejection and the isolation and defensive narcissism it can engender.

Among the funniest of the stories is the brightly colored ‘MCMLXVI,’ about a disaffected young adult male–who wears a ‘moptop’ hairstyle, like many a Clowes hero–obsessed with 1966, the year of his birth, who keeps his apartment “like a shrine to the golden age…the peak of American culture” and whose hero is “Adam West.”

Nearly friendless and revolted by almost every aspect of the present-day world, (including an older brother who performs professionally in drag as Madonna and a new near-friend who unfortunately asks, “Do you remember back when everybody was experimenting with bisexuality?”), he sustains himself with endless monologs about the horrors of modern culture. His closing advice to the reader is, “You’ve got to be able to go in your own direction or you get trampled by the flow of history…”

Another coming of age story, ‘Like A Weed, Joe,’ tightly encapsulates many of the themes and motifs found repeatedly in Clowes’s work. A lonely and thoughtful teenage boy, skinny and sporting another moptop haircut, is sent to spend the summer with his aging grandparents on a large lake.

When a family with a teenage daughter rents a cottage nearby, the boy becomes a peeping tom, watching the girl through a window at night from the bushes, and fingering himself when he discovers her wet bikini on a clothesline. He writes “I love you” in the sand on the lakeshore, even has his grandparents find him a companion in “moody and sinister” older boy Bemis, who is “a creep, plain and simple,” but who never pretends to be “otherwise.”

Influenced by Bemis, the boy coarsens superficially; his friendship with Bemis offers him an opportunity, however poor an opportunity, to step into manhood, even as his well-intentioned grandparents continue to take him to puppet shows and circuses as if he were a small child. Messages left in the sand for the boy are impossible to read when he comes upon them, and then the girl and her family leave. In the last panel, the summer over, the boy says, “I went to a new school where I struggled to be thought of as someone who housed a vital and complicated inner world.”

Loneliness, isolation, apathy, Jungian ‘introversion,’ frailty, obsession, the intelligence and perceptiveness of the non-herd animal, and the failure of human communication are common themes in Clowes’ work, and all are found in abundance in these unique and largely successful stories. While Clowes’ work is easy to understand and relate to, and often addresses common, even mundane, aspects of everyday life, it’s also true that very few Western writers can address such aspects as breezily and acutely, and pin them down as exactly, as Clowes does here. Who hasn’t been a “Carmichael,” known a “Mona Beadle”?

More than almost any other American writer working today, Clowes identifies, explores, and underscores both the deep and common aspects of “the pathological cruelty of everyday life” and ‘the little disturbances of man’.

Near mint, 1st print.

Related products

-

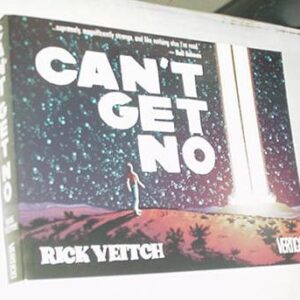

Can’t Get No TP Vertigo Rick Veitch Sept 11 9/11 NM 1st print

$69.99 Add to cart -

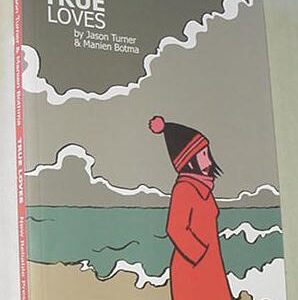

True Loves TP Jason Turner Manien Bothma 1st print

$49.99 Add to cart -

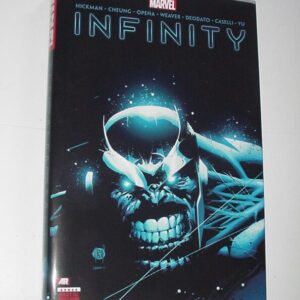

Infinity HC Omnibus Thor vs Thanos Hulk Jonathan Hickman 1st print

$199.99 Add to cart -

X Isle TP BOOM Andrew Cosby Nelson Greg Scott 1stp

$69.99 Add to cart