Description

The Republic of Plato Paperback

by Francis MacDonald Cornford (Translator, Introduction)

The Republic is a Socratic dialogue written by Plato around 380 BC concerning the definition of justice and the order and character of the just city-state and the just man.

Paperback: 366 pages

Publisher: Oxford University Press

I needed this book for a Philosophy Class, it helped me out, I thought I would help you all out and provide some locations to jump to:

Book I: 3954

Book II: 4707

Book III: 5335

Book IV: 6152

V: 6855

VI: 7712

VII: 8402

VIII: 9057

IX: 9752

X: 10332

I’ve been using the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Republic for three years now to teach freshmen, and Waterfield’s translation and endnotes are great. His choice to render dikaiosyne as “morality” rather than “justice” allows a range of discussion with American students that travels outside the courtroom and into the purpose of life and what translation means, and his crankiness in the endnotes (he talks about Plato as an old lover talks about his beloved) allows some great lessons about editorial practices and what’s involved in the production of a scholarly edition.

Plato’s Republic is unparalleled in its coverage of all areas of life. While Plato addresses metaphysical issues, he does so with language and analogies that most people can grasp with studious reading. But Plato talks about much more than metaphysics. Marriage, music, war, kings, procreation and more are all topics of discussion for Plato’s dialog. In addition to the teachings about life, this book also offers a great introduction to philosophy. The famous “cave story” illustrates not only the purpose of philosophy, but also the inherent difficulties. While this book is absolutely necessary for students of philosophy and religion, I think there are golden truths for all people no matter what they do.

So, why this particular translation of the work? This translation offers the best ease in reading while maintaining a tight grasp of the original Greek meanings of Plato’s text.

This book is clearly a timeless classic, and if you can’t read classical Greek, this translation is probably the best you will get.

Stickers on back cover and spine. Writing on inside cover and throughout book. Yellowing to edges of pages.

The House of the Seven Gables Hardcover – 1955

by Nathaniel HAWTHORNE (Author)

First published in 1851, The House of the Seven Gables is one of Hawthorne’s defining works, a vivid depiction of American life and values replete with brilliantly etched characters. The tale of a cursed house with a “mysterious and terrible past” and the generations linked to it, Hawthorne’s chronicle of the Maule and Pyncheon families over two centuries reveals, in Mary Oliver’s words, “lives caught in the common fire of history.”

“A large and generous production, pervaded with that vague hum, that indefinable echo, of the whole multitudinous life of man, which is the real sign of a great work of fiction.” –Henry James

Hardcover

Publisher: International Collectors Library (1955)

athaniel Hawthorne is probably one of the most despised figures in the American literary canon, at least in the minds of the millions of school children forced to read “The Scarlet Letter.” I will go so far as to admit I never finished that novel. I took one look through the book and laughed at the ridiculous idea of reading such a convoluted looking story. That was at age seventeen. Now, many years later I am able to go back and actually read some of these daunting novels. What is surprising is that they are not daunting at all, just written in an ornate style from a different age. The plots often deal with the same issues and concerns modern people fret about. For those uninterested in relationships and human dramas, there are also great old stories with supernatural elements, which is where this book comes in. This edition of the book includes an introduction by Mary Oliver and several commentaries on the work by Edwin Percy Whipple, Henry T. Tuckerman, F.O. Matthiessen, and Herman Melville. The Melville commentary is actually a letter the author of “Moby Dick” sent to Hawthorne where he concludes with a demand that Hawthorne “walk down one of these mornings and see me.” Pretty neat.

In “The House of the Seven Gables,” the author tells his reader the story is a romance. What he means by this terminology is not a cheap paperback that involves swooning hearts with Fabio on the cover, but “a legend prolonging itself, from an epoch now gray in the distance, down into our own broad daylight.” Hawthorne’s specific goal is to show that the bad behavior of one generation devolves on future descendents. He accomplishes this by examining the Pyncheon family, a clan founded on America’s shores by the stern Puritan Colonel Pyncheon, who used his considerable influence to inveigle prime real estate from one Matthew Maule in the 17th century. Pyncheon carried out this task by using the Salem witchcraft scare to secure Maule’s execution. In his last moments, Maule laid a curse on the good Colonel and all of his descendents, telling him that God would give them blood to drink as a punishment for this evil injustice. Shortly after the Colonel builds his house with seven gables on Maule’s property, he dies in a way that makes Maule’s curse seem to be a reality. Rather than trace this terrible evil down through the ages in minute detail, Hawthorne only touches on a few important points before beginning his story in the middle of the 19th century.

The Pyncheon family is slowly moldering into extinction when Hawthorne introduces us to poor old Hepzibah Pyncheon. She lives alone in the ancient estate, reduced to near starvation because her brother Clifford is in prison and Jaffrey Pyncheon, a rich judge who lives in his own manor in the country, refuses to offer her assistance. The only way to survive for Hepzibah is to open a penny store in an old part of the decaying house. Just when things reach a nadir, another Pyncheon turns up to save the day. This is Phoebe, a vivacious young lady who lives in the country. This fetching lass is a blessing for Hepzibah; she runs the penny store, helps to lift the gloomy atmosphere in the house, and when Clifford returns from his long imprisonment, Phoebe entertains the doddering man with her multitude of charms. She even strikes up an acquaintance with Holgrave, a young boarder in the house. Things start to look up when yet another tragedy strikes the Pyncheon family, leading to the momentary evacuation of the ancestral estate by Hepzibah and Clifford before Hawthorne settles all accounts in an ending that is both quick and highly implausible.

I personally enjoyed the deeply rich 19th century prose. Hawthorne’s command of the English language is impressive and, at times, as precise as a cruise missile. One need only read the chapter about Judge Jaffrey Pyncheon’s unfortunate incident in the house to grasp the beauty of this author’s style. As for the digressions, if people have a problem with chapters such as “Alice Pyncheon” and the introductory material setting down the history of the doomed family, it is really their loss. It is when Hawthorne writes about supernatural elements that he really managed to grab me. If this counts as a lengthy digression from the story, I will take more, please!

If I had to assign a Hawthorne novel to a group of slack jawed high school students, I would give them this one in place of “The Scarlet Letter.” At least with “The House of the Seven Gables,” someone might enjoy the eerie curse that united the Maules with the Pyncheons for two centuries. A letter sewn on clothing cannot stack up against ghosts, a disembodied hand, and mysterious deaths. The kids will still grumble, but not as much when they realize there are less “thees” and “thous” tossed around in this novel.

Book is in near mint condition.

Book is in near mint condition.Book is in near mint condition.

Related products

-

Get Into Graduate School 4th Edition SC Kaplan 2011

$39.99 Add to cart -

Business A Changing World 6E SC Ferrell Hirt McGraw Hill

$49.99 Add to cart -

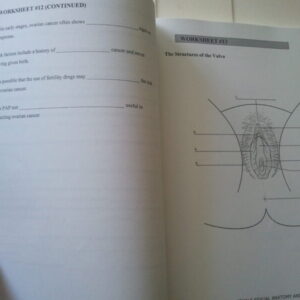

Examining Concepts in Sexuality Workbook SC Rosemary Iconis

$49.99 Add to cart -

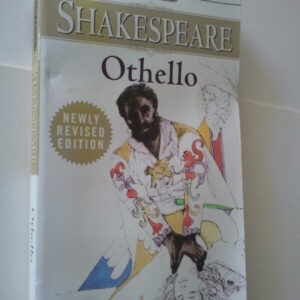

Othello Newly Revised Edition SC Shakespeare Signet Classics Alvin Kernan Critical Essays

$19.99 Add to cart