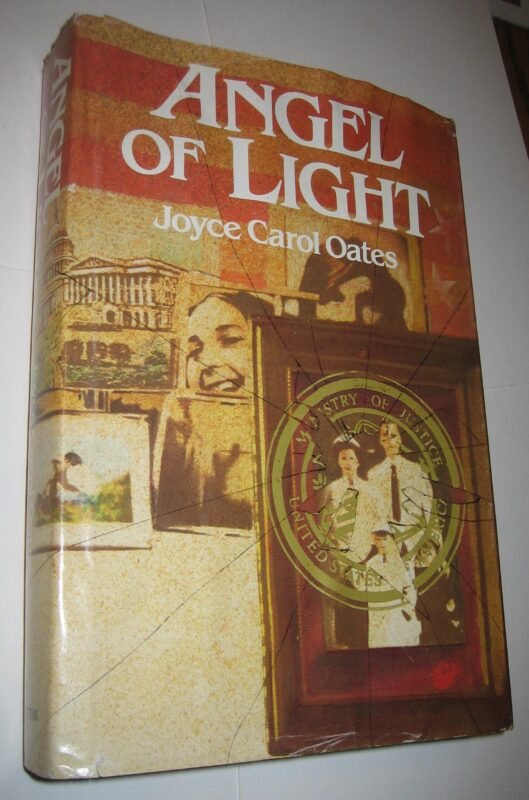

Description

Angel of Light Hardcover

by Joyce Carol Oates (Author)

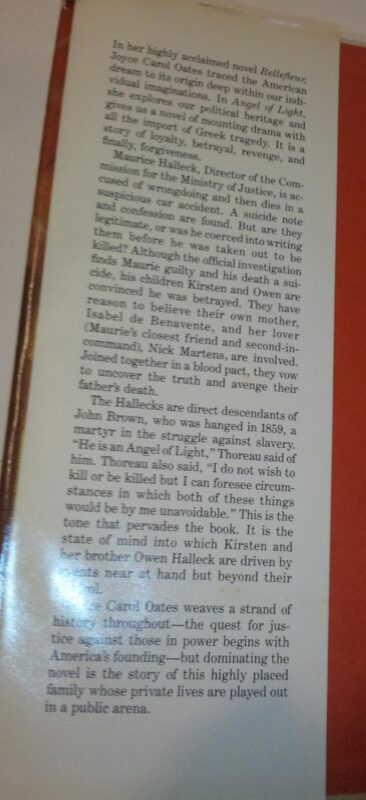

When Maurice Halleck, a minister of justice accused of corruption, dies an apparent suicide in a car accident, his children, believing he was betrayed by their mother and her lover, seek revenge

Hardcover: 434 pages

Publisher: E. P. Dutton; 1st edition

Politics. A failed marriage. The intricate world of Washington in the years of 1979-1980, without naming names, a gentle gloss over realities. The politics is just a backdrop, however, for the Halleck family. Maurice, the head of the family, leaves a drunken, convoluted confession and his car is found in a brackish swamp in a small Virginia town. His children, Owen and Kirsten, are convinced it is the doing of his wife and his long time friend (and wife’s lover) Nick; everyone else is convinced it is a suicide due to his unscrupulous practices in D.C. The story follows the children and their plans to exact justice however they can.

The characters are well written and realistic, and it is a satisfying read.

With 12 novels and 11 books of stories published within the past two decades, Joyce Carol Oates must be our most productive writer of serious fiction. Like such other big producers as Doris Lessing, John Updike and Norman Mailer, she recalls an old-fashioned idea of the novelist as one who does not occasionally unveil a carefully chiseled ”work of art” but who conducts a continuous and risky exercise of the imagination through the act of writing. Where a new novel by John Barth, Saul Bellow, Joseph Heller or Thomas Pynchon is deemed, whatever its merit, a literary event, a new novel by Joyce Carol Oates is, we may feel, another new novel by Oates, better or worse than the last one, certainly different from it, but hard to see as a major demand upon our attention. This immediate response is unfair but perhaps not lasting. With occasional exceptions (Joyce, Flaubert), we finally care most about novelists like Dickens, George Eliot, Balzac, Tolstoy, Hardy, James, Conrad, Lawrence or Faulkner whose work is copious enough to constitute a ”world,” and though no guarantees can be offered, energy like Joyce Carol Oates’s may find an eventual reward. Text:

Her newest book, ”Angel of Light,” is a political novel, though one less interested in the practice of politics itself than in its power to evoke certain deep human impulses toward violence. The story is very generally based on the fall of the House of Atreus; once again a brother and sister seek to avenge the killing of their father by murdering their mother and her lover. But here the myth is updated, and altered, by the terms in which power is now exercised inAmerica – the shadowy intersections of government, business, finance, ideology and organized crime.

Maurice J. Halleck, a rich, idealistic public servant, director of the Commission for the Ministry of Justice, is in the late 1970’s suspected of having taken a bribe to quash an investigation into a major corporation’s illegal political interventions in South America. Halleck resigns, separates from his society-hostess wife, takes to drink, and finally, in June 1979, commits suicide, leaving behind a confession of his guilt in the bribery scandal. His daughter Kirsten, a disturbed, anorexic, drug-dependent boarding-school girl, is sure that her father was innocent. Without hard evidence, she just knows that his confession was forged and that he was murdered by his wife, Isabel, and the ambitious Nick Martens, his friend since school days, his assistant and then his successor as director, and by general belief Isabel’s lover for many years. Kirsten persuades her brother Owen, a smug, suc-cess-oriented senior at Princeton who is bound for Harvard Law and a career like his father’s, that her terrible, improbable imaginings are true, and together they plot to serve justice by killing Isabel and Nick.

Miss Oates gives this grim story an epigraph from Bernard Mandeville, the 18th-century master of a moral ”realism” cunningly designed to be both heartening and profoundly demoralizing: ”What we call Evil in this World, Moral as well as Natural, is the grand Principle that makes us sociable Creatures, the solid Basis, the Life and Support of all Trades and Employ-ments without Exception: That there we must look for the true Original of all Arts and Sciences, and that the Moment Evil ceases, the Society must be spoiled if not totally dissolved.” But if the ”Angel of Light” is a philosophical novel about the impossibility of justice in a fallen, irredeemably compromised human community, the book (in a good 19th-century way) accommodates other kinds of interest too – it is at once a kind of thriller, a romance of desire and betrayal in high society, a psychological examination of alienated youth, a study ofmarital failure in a declining aristocracy, an uncovering of the personal roots of public violence.

The narrative relies on temporal crosscutting, between the six months in 1980 during which the children conceive and pursue their plot of revenge and flashbacks of Maurice Halleck’s life as it is woven into the lives of Nick, Isabel and his children. It all began in 1947, on a white-water river in Canada, when Halleck, a rather inept and unprepossessing rich kid with deep religious yearnings, was saved from drowning by Nick, his capable, attractive, fiercely competitive prep-school friend, a scholarship boy whose future is assured by the gratitude of Maurie and his family. This first bonding is complicated by Nick’s later testings of Maurie’s devotion. In 1955, when Maurie first introduces Nick to his provocative fiancee, Isabel, the two disappear together for a suspiciously long walk on the beach; in 1967, watched by a fuming Isabel who has a party to give, Nick and Maurie play an interminable tennis match, protracted because Nick, who is normally much the better player, is determined to win the last game but somehow can’t; just before his death in 1979, Maurie struggles to understand and accept what his final talks with Isabel and Nick have revealed, that he has been less central to their lives than he realized. And while this history approaches the catastrophic present, the Halleck children -Orestes and Electra in Washington – pursue their bloody design without knowing clearly how the past has created, and betrayed, the present.

I’m not sure that Miss Oates adds a great deal to what writers like Louis Auchincloss, Frederick Buechner, John Cheever and John Knowles have told us about the moral life in our old ruling class. Even at their most vivid moments – as when the aggressive Nick confesses a secret yearning to be not himself but just ”a person,” without family, history, or intentions – Miss Oates’s adults may owe as much to other fiction as to fresh observation or imagining. But the story centers on Owen and Kirsten, and their search through violence for an exactitude of justice that, as Mandeville suggested, no human society could survive. In her portrayal of the Halleck children, Miss Oates achieves a fresh and frightening picture of a desire that exceeds any available attainment. Owen and Kirsten, whom Miss Oates makes descendants of John Brown of Osawatomie, strive to reconstruct reality in the image of their dream of justice, as their ancestor had once also tried to do, with equally shattering effect.

Thoreau provided the title for this novel when he called John Brown ”an Angel of Light,” and we may safely presume that, like Joyce Carol Oates, Thoreau was cognizant of who the first angel of light was and what befell him. One of that Lucifer’s stoutest champions, William Blake, in fact presides over Owen and Kirsten’s great enterprise; they debate, with touching uncertainty, the meaning of various of Blake’s ”Proverbs of Hell” before finding one whose significance unarguably suits their purpose: ”What is now proved was once only imagined.” For them this suggests that destructive action can confirm and justify their conviction that their father was framed and killed by a wife and friend who served not only their own paltry desires but also served (somehow) a conspiracy of the power structure, whose identification of realpolitik with reality was threatened by Maurice Halleck’s almost saintly probity.

We are for a while free to regard the children’s imaginings as being just what they sound like, a fantasy born of grief and precarious stability. Kirsten was a wild, self-destructive girl long before her father’s fall, and in the pompous, buttoned-down conformity of boys like Owen there often does lurk a repressed other self nearing critical mass. And, of course, public events in the children’s formative years engendered paranoid delusions in older and sounder minds than theirs. Since suspense is one of the book’s pleasures, I must not say too much here; but it does start to appear that the children’s imaginings may not be as utterly fantastic as they seem. There are real questions about Halleck’s guilt, about Isabel’s virtue and Nick’s loyalty, even about how remote this personal tragedy is from political and corporate maleficence. If what begins to be proved is not exactly what once was only imagined by Owen and Kirsten, in a social world regulated by Evil, some uncomfortable possibilities do suggest themselves. In such a world exact proof is hard to come by -one seemingly knowledgeable source says that Nick was a C.I.A. agent, while another claims that he was an undercover Communist, and he may have been neither, or both – but such indeterminacy itself hints at moral horror. On the other hand, those who would dissolve ambiguity into single vision by an act of moral will point toward an alternative and commensurate horror – here exemplified by the American Silver Doves Revolutionary Army, a group of underemployed ex-graduate students turned Maoist terrorists who convert Owen’s personal quest for justice into service in their own violent cause .

Having recently seen so good a novelist as Mary McCarthy turn somewhat similar material into a talky, unconvincing ideological puppet show in ”Cannibals and Missionaries,” I’m much impressed by Miss Oates’s ability to enter and explore the personal sources of the high-minded violence that’s now such a familiar fact of public life. I’m impressed too by how clearly she remembers that her first duty is not to judge but to understand. Judgment of a kind is suggested, particularly in the novel’s epilogue, where a survivor of this children’s crusade, living alone and unoccupied on the coast of Maine, ponders ”the emptiness and beauty of a world uncontaminated by, and unguided by, human volition”; but if the choice of solitude and a resigned acceptance of the world as a mystery whose secret is not to be discovered constitutes a form of judgment, it is not one that offers ready comfort.

”Angel of Light” may be another chapter in Joyce Carol Oates’s ongoing exercise of the imagination, but it is also a strong and fascinating novel on its own terms. Coming after her haunting fantasy ”Bellefleur,” which in effect levitates above the history and geography of the known world to report that its larger moral contours remain deeply mysterious, ”Angel of Light” gravitates back toward the terra firma of a novel like Miss Oates’s ”them,” where social circumstance and personal fate are closely and realistically linked. But enough mystery persists in ”Angel of Light” to suggest that this prolific and various novelist is staking out new fictional ground.

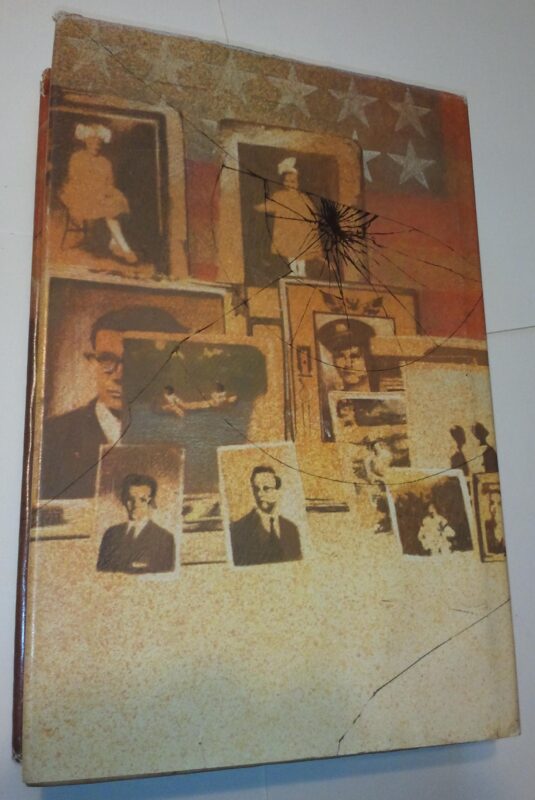

Shelf wear to dust jacket. Outside of pages have picked up dust. 0-525-05483-9.

0-394-55023-4

Partial remains of sticker on cover. Small tear in dust jacket at bottom of spine. First edition.

Related products

-

African Arts & Cultures HC Jacqueline Chanda Davis Publications 1993

$74.99 Add to cart -

Business Law Today 7th Edition Study Guide SC Hollowell Miller Thomson

$49.99 Add to cart -

AP European History Testware Edition 10th Edition SC REA

$49.99 Add to cart -

Tales From The Fish Camp TP NM OOP Danielle Henderson

$69.99 Add to cart